My first daughter is a senior at UCLA, due to graduate in a few weeks with a degree in Materials Science and Engineering. A few of weeks ago, she and her 4 other research group members after their capstone project completion went out to eat together at Sun Nong Dan (선농단) in Koreatown at the suggestion of another member (with my daughter being the only Korean in the class). This LA-only spot specializes in beef (bone) soup and galbi-jjim (braised short ribs).

This particular dish, apparently devoured clean with two bowls of rice each by two male members of the group, can be prepared in two ways—not spicy (soy sauce-based) and spicy (gochujang-based). Regardless of which one you choose, you will probably crave something sweet to balance out your palate—these do have strong flavors.

Towards the end of the meal, my daughter calls and asks me, “아빠 (appa, “dad”), do you know of a Korean dessert cafe around here?” Apparently, the group members wanted to go full Korean that night.

Korean desserts, you say? It may not be very well known, but we do indeed have them, and I would like to introduce some of them, both traditional and modern, today.

(BTW, that research team of 5 have some serious brain power among them. 4 of the 5 are moving on to Ph.D. programs—my daughter to Northwestern, one guy to Cambridge (yeah, that one in UK), one guy to University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and one other gal to Georgia Tech, all top programs in the field.)

Fruits and Dried Fruits

No explanation necessary and the most readily available throughout the year. However, I would like to show you one particular dried fruit that is a popular Korean dessert item. Persimmon is called 감 (gahm) and when it’s dried, it loses all the tannin (that sort of bitter and dry flavor of the red wine when you first open it) and becomes cinnamon-y sweet and chewy in texture. The dried persimmon, called 곶감 (goht-gahm), is sometimes cut open, seeds removed (if any), laid flat, and rolled with walnut pieces inside. One of my absolute favorites.

Korean pears and strawberries in season are not to be missed. My hometown of Geochang is famous for the sweetest strawberries and apples.

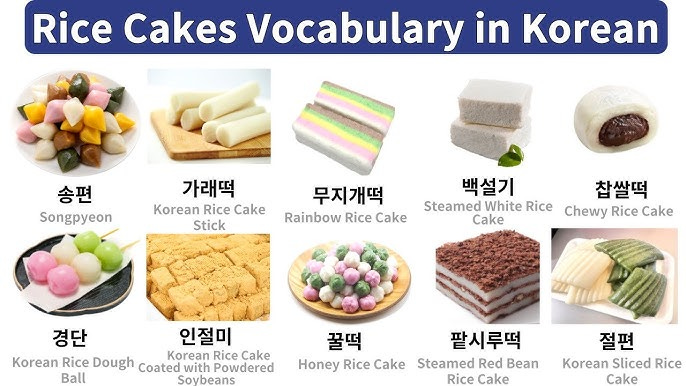

Rice Cake (떡, tteok)

This is probably the most accessible and widely consumed Korean dessert there is, the likes of which deserves its own blog topic. You may be more familiar with the Japanese mochi, which is basically the same thing.

There are so many different types of tteok that I cannot possibly write about all of them, ever, but just to give you the very basics, rice is first steamed then beaten with a big wooden mallet to turn it into a thick paste-like (cake) consistency. Then, all sorts of fillings, the most popular being sweetened red beans called 팥 (paht), are added to make the finished product.

I used to not like these when I was little but as I get older, I sometimes find myself craving them. It’s weird how your taste buds change as you age. The general rule of thumb is that tteok should be consumed on the same day it’s made. Otherwise, because it’s made of cooked rice, they lose moisture and flavor, and get dry and hard to chew on. They’re mostly very mildly sweet, with some of them being not sweet at all.

Hardened Malt (엿, yeot)

Our ancestors, east and west, knew how to extract sweet material out of malt (sprouted barley) and use it for various cooking purposes. Because sugar was obviously not available, or prohibitively expensive, in the old days, this was the main sweetening agent. The malt would be cooked in low heat for a few hours, cooled, then hardened to form this “yeot,” which was apparently cheap enough for even the common folks as far back as a thousand years ago in Korea. Different ingredients are added to make variations of yeot such as pumpkin yeot (호박엿), pine nut yeot (잣엿), sweet potato yeot (고구마엿) and such. These are actually harder to find these days. Be careful when you eat it though, it’s very hard—people have broken their teeth trying to bite down on it.

Yak-gwa (약과)

This once royal-court only dessert made of wheat flour (rare and expensive a few hundred years ago), liqueur and honey, fried in oil (again, rare and expensive) is sort of making a comeback with many Korean pâtissiers these days. A must-have on any jeh-sa table, this is actually easy to find at any Korean supermarkets.

Ho-tteok (호떡)

These may look modern but in fact they are very old traditional Korean dessert, most probably imported from China or Persia almost a thousand years ago.

If you’ve been to Korea, I’m sure you’ve seen something like the above picture at traditional markets. These light snack, featuring a cross between tteok and bread dough, are filled with cinnamon sugar and crushed nuts (if you’re allergic to nuts, stay away because almost all variations have some sort of nuts in them) and fried in a shallow pool of oil.

I can’t get enough of these if I didn’t have to worry about the weight gain. Very affordable too, usually about 1500 KRW (~$1 USD) per piece.

Gahng-jeong (강정)

A prototypical traditional Korean dessert. All sorts of grains, nuts, seeds are first cooked or toasted, smothered in malt syrup (liquid 엿), shaped, dried, then cut into bite-sized pieces. I grew up with these (my grandmother used to make these at home) and never liked it—I still don’t.

Tteok-bokki (떡볶이)

Believe it or not—these used to be a dessert/snack item for the Joseon royal court. The name itself means, “stir fried tteok.” The spicy red kind that everyone knows of came into being only about 6 decades ago—the original version of tteok-bokki for Joseon royalty was soy sauce-based with malt syrup or honey.

Shik-hye (식혜)

Let’s get to two most popular traditional sweet drinks. One is called shik-hye and it’s made with steamed rice, liquid malt (there it is again) and water, left to ferment in ong-gi (옹기). It has distinct similarities to horchata. A glass of ice cold shik-hye during a hot muggy summer day in Seoul can be a lifesaver.

Soo-jeong-gwa (수정과)

The other is this ginger/cinnamon/honey/persimmon “tea.” If you like strong cinnamon-y flavor, you will love this.

A few modern desserts

Dalgona (달고나)

Dalgona stalls seemed to be at every street corner when I was in grammar school but they all but disappeared in the 1980s when the Korean economy started growing in a major way and all the factory-made inexpensive confectionaries started making inroads.

Then the mega-hit Netflix drama Squid Game came out… and the rest, as they say, is history. It popped up everywhere but I think the craze has faded out. All it is is melted sugar with a tiny bit of baking soda—that’s it!

Bing-soo (빙수)

I think a lot of cultures have a version of this under the name of “shaved ice.” The Korean version is characterized by the liberal use of the sweet red bean paste called paht (팥, “red bean”) and was first introduced sometime during the Japanese Occupation era in 1930s.

Recently, this has evolved into an art form—if I had to pick one Korean dessert item (I’m not into dessert all that much, btw) for the rest of my life, I’d choose bing-soo. “What kind?” is a whole another question because I think there are literally hundreds of different types.

This is the menu from a very popular bing-soo cafe in Koreatown called Sul & Beans in Los Angeles. Just from one store—and this place is always packed with customers.

Boong-eoh ppang (붕어빵)

Originated in Japan as “taiyaki,” meaning literally “baked snapper,” this is a pastry with, yet again, sweet red bean paste in it. Boong-eoh (붕어) is a Korean indigenous smaller species of freshwater carp.

This has also evolved over the years. Instead of the usual sweet red bean paste, now there are custard cream, sweet potato cream, japchae noodles, and pizza sauce/toppings as fillings. I couldn’t bring myself to try the new ones, but I’ve heard it’s actually not bad at all.

I looove rice cakes, but I usually eat a salty version with veggies. Which reminds me that I still have some in the fridge...tomorrow´s dinner is then assured !