Let’s start off with a monumental work of Kim Hong-do and his Royal Court artist associates who, in great detail, painted King Jeongjo’s procession to Suwon1 to celebrate his mother’s 60th birthday.2

63 pages in total after restoration, the entire painting was left in a scroll form and is more than 100 meters long (over 330 feet).

As for the procession itself, King Jeongjo (정조, there are tons of stories about him that I will have to get to eventually) in 1795 put together an extravagant fanfare not only to celebrate his mother’s birthday but also to stage a show for the common folk. All records indicate that the event was like an enormous national party.

All told, in this 8-day procession, about 6,000 Royal Court personnel took part in it, including high ranking officials (equivalent to today’s cabinet members), mostly military guards, servants, and livestock. Close to 2,000 of them were all individually depicted in good detail, with their official titles and their uniforms, in this more of a visual historical record than a painting. A lot of Kim’s works are like photographical records of what things were like 250 years ago.

The National Museum of Korea has a dedicated wrap-around widescreen theater that features a compilation of a few well-known artworks of the Joseon period that’s been digitized into a moving animation. Pay special attention to the first four minutes of this VR 360 YouTube video, for it shows the famed royal procession in a lighthearted, fun sort of way. It’s best to watch it in full-screen mode.

I was reading something about the superbly fascinating British poet and painter William Blake, and it made me think that he and Kim Hong-do had something in common in a strange way (just my personal opinion). They were both heavy on symbolism (so I’ve read) and had a mysterious aura about them. You may have seen some of Blake’s works without realizing it, for they’re trivially displayed in shirts, posters, and other visual materials.

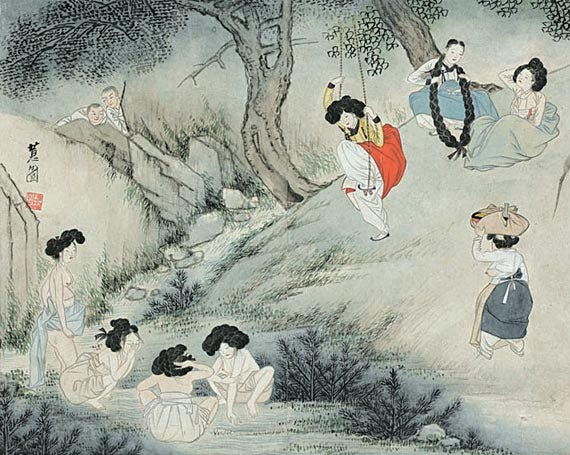

Held in the highest esteem as one of the two greatest painters of Joseon Dynasty by the Korean academia, Kim left some masterpieces on the historical records and genre paintings, as well as a thick collection of smut (of course no one talks about this and you can find a whole bunch of them on Google Arts & Culture).

The above paintings are two of Kim’s most well-known works and we’ll get to the enigmatic part of Kim shortly.

Before we get into it, let’s briefly go over what the art scene was like in Joseon. I know very little about it—regurgitating what I learned in school from geez… 40 years ago.

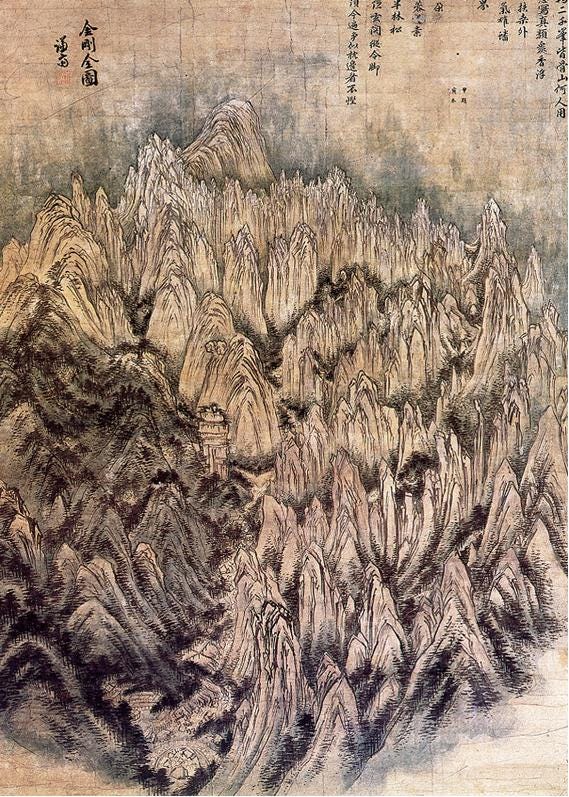

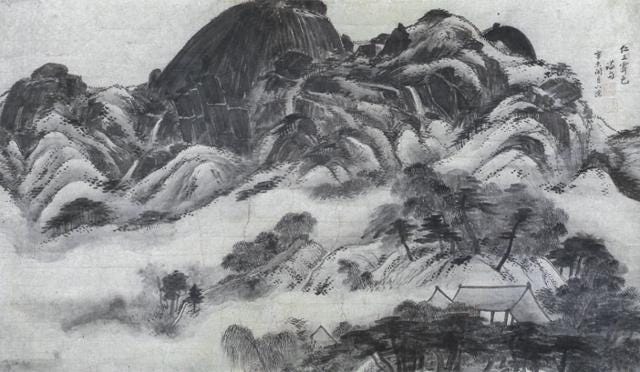

The above is the work of an early Joseon period artist An Gyeon (안견, 15th century), and the following two are masterpieces (so they say) of Jeong Seon (정선), of early 1700s.

I’m sure you’ve all noticed that most of these Joseon-era paintings are monochromatic—there are no colors to speak of. This despite…

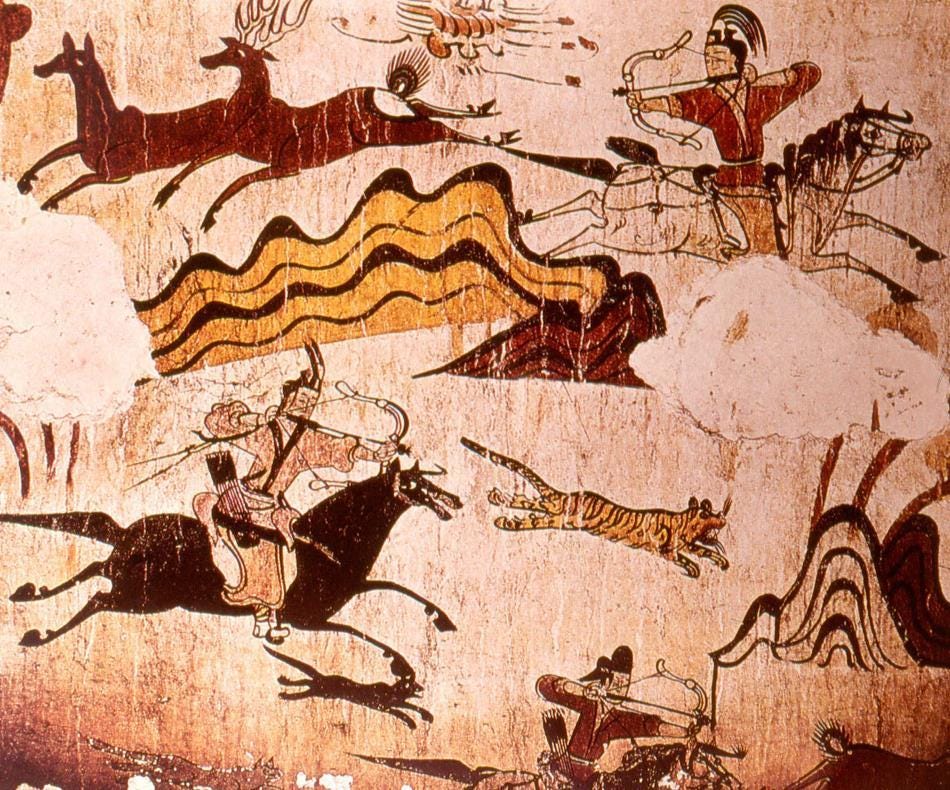

… full color fresco from Goguryeo (고구려) dynasty, circa 6th century. And…

… full color Buddhist paintings from Goryeo (고려) dynasty, circa 9th~10th century.

It is quite clear that the monochromatic artwork of Joseon is not due to the lack of color materials. During the time of the strict Neo-Confucian Joseon dynasty, creativity was discouraged and conformity was the rule, under the artistic philosophy of…

시서화일치

poetry (시), writing or books (서), and painting (화) are born of the same origin (일치)

So, it was only natural for the Joseon scholars/painters to do all three on the same piece of paper (canvas) with one brush, one color. This is precisely why you frequently see writings (often times poetry) on the paintings.

The two people who broke away from this centuries-old tradition in painting were Kim Hong-do and Shin Yoon-bok, who lived in the same time period with Kim being 14 years older (late 18th to early 19th century).

Anyway, it still remains a mystery to this day but Kim Hong-do left some tantalizing twists in his paintings.

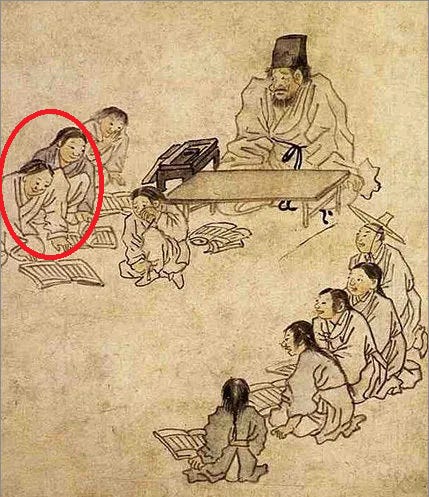

In a lot of his paintings of his day’s scenery, Kim either knowingly or unknowingly drew certain body parts in opposite sides, and in unnatural positions, sometimes with missing or extra digits. For example, you see the man’s right hand in the left-hand position and vice versa. He also drew figures of Buddha with 6 toes.

Another example: the right leg of the boy with the purplish shirt and the left arm of the boy next to him are one and the same. There are many other instances in which Kim does this. Granted, these are not some grandiose themed hidden symbols in the level of William Blake, but curious (or something deeper?) nonetheless.

There are a few theories in the art world as to why Kim did this. 1). He suffered from what’s called Gerstmann Syndrome where a person has difficulty differentiating left from right and vice versa and/or recognizing fingers and toes, 2). He was playing a game with his artist friends to see if they could spot it, 3). He purposely hid these “mistakes” to authenticate his works from other would-be imposters.

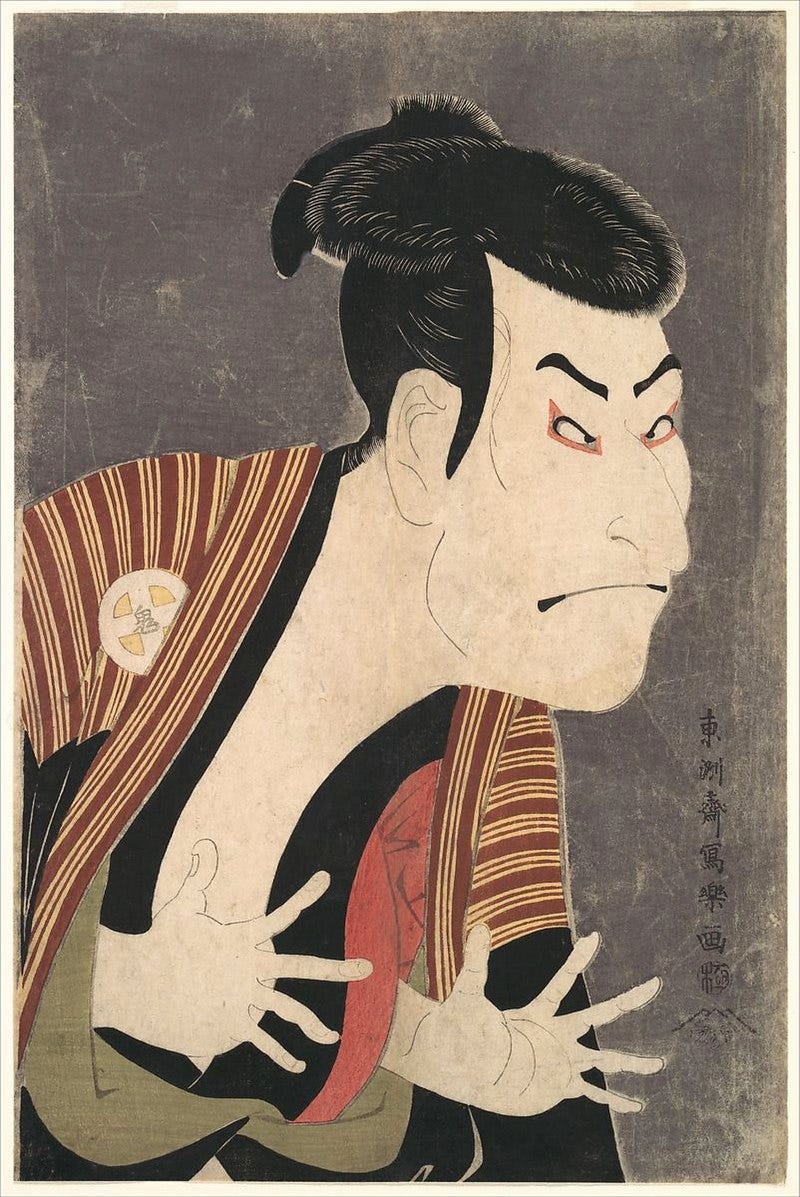

With that, let’s move on to the biggest mystery surrounding Kim. You may not know the artist’s name, but you may very well have seen this portrait of a Japanese kabuki actor from the late 18th century.

This work is signed by someone named Toshusai Sharaku (東洲齋寫樂). This is the first paragraph of Sharaku, as he is popularly known as, in the Wikipedia page.

As I understand it, there are about 30 different people who’s been rumored to have been the real Sharaku. Kim Hong-do is one of them. Korean scholars say that it is very unlikely, but there are indeed a number of compelling reasons for that argument, although the Japanese academia thinks it’s someone else.

First, the name. The artist’s fake last name (東洲齋) means, “House in the eastern land.” (Japan is east of Korea.) The first character of the first name Sharaku (Sah-rak, when read in Korean) has the same pronunciation Kim Hong-do’s other name 사능 (Sah-neung). And the middle name character raku (rak read in Korean) is one of the characters of the region Kim Hong-do was a local magistrate in. Okay, so far, this is a bit of a stretch.

Second, that 10-month active period of this Sharaku person from 1794 to 1795 coincides exactly with the time when Kim was known to have been dispatched to Japan by King Jeongjo on sort of a secret mission. Okay, this is starting to get interesting. As prolific a painter as he was, there is about a 10-month period right around that time during which there is no painting accredited to Kim in Korea.

Third, see those fingers of the kabuki actor’s portrait? Do they remind you of someone’s very unique style? i.e. Gerstmann Syndrome? I can’t find any of the images, but Sharaku also drew certain figures with 6 toes.

Fourth, there are writings on some of Sharaku’s paintings. Those are supposedly incomprehensible gibberish from the Japanese language perspective, but can be interpreted by using something called ih-doo (이두), an ancient Korean writing system using converted Chinese letters. (although this point has mostly been debunked by Korean scholars.)

Where his father—Crown Prince Sado—was buried. One of the craziest and most tragic stories in all of Korean history.

60th birthday used to be a huge deal—not many people lived that long a few hundred years decades ago.

Thank you for the video link; amazing animation and sound track. AI at work?

Nice article about Kim Hong-do's art and a fun venture into the possibility that Sharaku could have been Kim Hong-do. I also enjoyed the painting of 씨름 (ssi-reum), having just become familiar with the sport of Korean wrestling. This article is full of Korean cultural history. 감사