Linguists classify Korean under the category of Koreanic language, meaning that it is a unique language that does not belong in any larger or related linguistic families. As a point of reference, most of the European languages (English, Spanish, German, French, Portuguese) are related to one another but Korean isn’t related to the Chinese nor the Japanese language, although there are similarities in Korean and Japanese grammar.

But I would be remiss if I didn’t recognize the written Chinese language as having a huge influence on the Korean history, culture, writing, and naming systems. That point isn’t refutable. The same goes for the Japanese history, culture, and language as well. In fact, the Japanese writing relies a lot more heavily on the Chinese writing system than Korean does.

You must understand this linguistic background to fully appreciate how unique the name “Seoul” truly is. But for the sake of generalities, we’ll talk about how the name “Korea” came into being first.

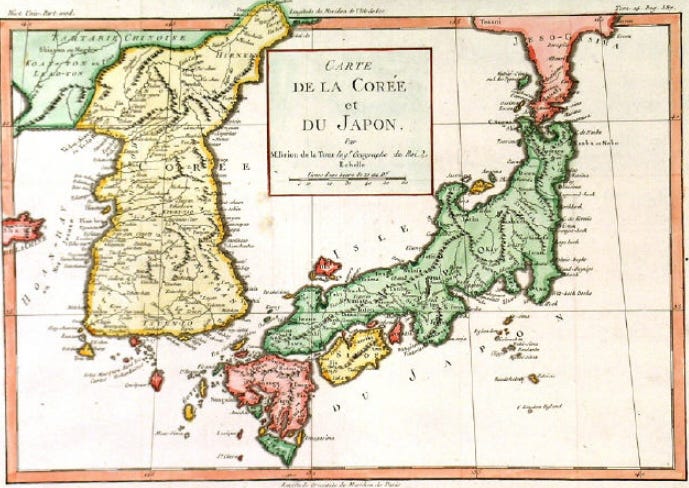

In previous postings, I’ve talked about a few dynasties that Korea has had over its 5 millennia history. One of those dynasties is 고려 (高麗, 918 ~ 1392), which is spelled in different ways; Goryo, Koryo, Goryeo, Koryeo. As you might have guessed, the name “Korea” comes from the anglicized version of 고려, whose existence was first introduced in Europe during the 11th century. (BTW, this is a point of contention but we’ll stick with this version because it’s simple and highly plausible.) And the name has obviously become the country’s international identifier ever since.

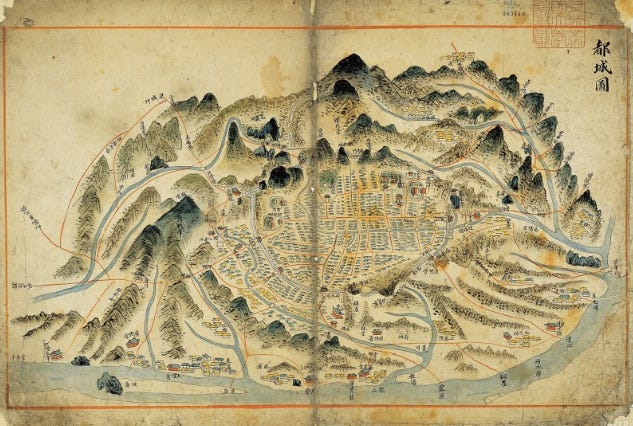

The city of Seoul has had many different names throughout its history. In the ancient days about 2000 years ago, the general vicinity (because it wasn’t established as a city back then) was called Han-sung (한성, 漢城) or Wi-rieh (위례, 慰禮). It was even called Nam (south) Pyong-yang (남평양, 南平壤, yes, that Pyong-yang in North Korea) during the time of Goguryeo. Then, it was known as Yangju (양주, 楊州) during the Goryeo dynasty, and of course Han-yang (한양, 漢陽) during the Josun dynasty. After Josun fell to the Japanese imperialists, the name was changed to Gyong-sung (경성, 京城). And finally, one year after regaining national independence in 1945, the capital city was named Seoul, or 서울.

Do you notice something different about the current name Seoul from the group of its old names that I’ve listed above? (Give it 3 seconds…)

You may or may not have noticed it, but I have tried to utilize 3 languages when describing a name of something—English, Korean, and Chinese—in all of my postings. Doing so can make reading difficult sometimes, I know, but I felt that there was value in bringing the entire picture of describing something.

To answer the above question, the name Seoul does NOT have corresponding Chinese letters like most other names do. It is thus called “Pure Korean (순우리말, soon-woori-mal).” It is the ONLY pure Korean named city in the entire country(!!) and I think it’s important to recognize that.

OK, that was a way too long-winded preface to the topic of the day—where the name Seoul comes from. The first dynasty that unified the Korean peninsula was Shilla (신라, 新羅) that lasted about a thousand years, from 57 BCE to 935 CE. The capital city of Shilla was called Seo-ra-beol (서라벌, 徐羅伐) which is modern day Gyongju (경주, 慶州) in Gyongsang Province. Gyongju is often described as an open museum without a roof, meaning the entire city is like a museum. It is still being explored and excavated for historical artifacts and treasures. The city itself deserves at least 5 different postings but I’ll defer for now.

Anyway… the name Seo-ra-beol, which of course is a proper noun, over the long reign of Shilla, sort of became a common noun meaning “capital city.” And to reflect that, according to a book published during King Sejong the Great in 1447, there is a reference to the word “셔ᄫᅳᆯ (like “shovel” but with a b instead of v”) to refer to a capital city. The archaic second character (that looks weird) has a consonant “ㅂ” sitting on top of another consonant “ㅇ”, which doesn’t exist in modern Korean grammar. That word, derived from Shilla’s capital city, has evolved over the years to become Seoul, or 서울.

Now let’s talk about the names of South Korea’s Provinces (like States in US or Cantons in Switzerland). I’m going to start from the south and move up, and not include Jejudo and Gyonggido in this discussion for the sake of uniformity because those 2 provinces have a different naming history.

First, here’s the map of South Korea, from the Korean portal Daum, stuff written in Korean.

The red rectangles are the names of Provinces. And I’ll get to that red down arrow in the Gyongsang-do section little bit later.

The following is from the Google map, stuff written in Korean and English. Before we get into it, there is something you need to understand about the English anglicization of the Korean names. 전라북도 is spelled as “Jeollabuk-do” because that’s how 전라북도 is pronounced, not written. The way it’s written in Korean, it should have read “Jeon-ra-buk-do” but this has to do with some basic rules of the Korean language and grammar, and we’re not going to get into it here. Again, it helps to learn to read basic Korean. I’ll do my best to use both Korean and English to try to explain it.

Three words you need to know—buk (north, 북, 北), nam (south, 남, 南), and do (province, 도, 道).

OK, Jeolla-do (or, Jeonra-do), buk or nam, is written as 전라도 or 全羅道 in Chinese. See the two circled cities in the map? Jeon-ju, and Na-ju?

전주 (全州) + 나주 (羅州) = 전라도 (全羅道)

Jeon-ju + Na-ju = Jeon-ra do (Jeolla do)

One basic grammatical rule about Korean language. The first consonant of a Korean word cannot begin with the “ㄹ (r or l)” alphabet. It automatically becomes “ㄴ (n)” alphabet. This rule doesn’t apply to words that are of foreign origin such as 라디오 (radio) or 로스엔젤레스 (Los Angeles). That’s why 羅州, which is actually 라주, is officially written as 나주 (Na-ju), not Ra-ju or La-ju. If you remember that “ra, 羅” character is used in the Shilla Dynasty, and is NOT read or written as Na because it’s not the first consonant of a word—it comes in the middle. (Confusing? Absolutely. Perhaps I did a piss-poor job of explaining it—apologies…)

Let’s move on to Gyongsang-do, 경상도, 慶尙道. Exact same thing here.

경주 (慶州) + 상주 (尙州) = 경상도 慶尙道

Gyong-ju + Sang-ju = Gyongsang-do.

See that little square to the left of the map that says Geochang, 거창? That’s where I’m from. When I say, “I grew up in a small town in southern Korea…” that’s where I’m talking about. Northwest corner of Gyongsang-nam-do. V of BTS grew up here as well—he went to elementary school here apparently, but he lists his hometown as Daegu, a lot bigger city 50 miles away. (I mention this only because he’s the first and the lone celeb that’s come out of this small town.)

OK, slightly up north, Chung-cheong-do, 충청도, 忠淸道. Again, exact same thing.

충주 忠州 + 청주 淸州 = 충청도 忠淸道

Choong-ju + Cheong-ju = Chung-cheong-do

Choong-ju (or, Chung-ju) is not shown on the above map, so I marked it with the small red triangle, right under the letter K of BUK.

And to the east of South Korea, Gangwon-do, 강원도, 江原道. This province is not divided into North and South. It’s just one big Province that stretches into North Korea as well.

강릉 江陵 + 원주 原州 = 강원도 江原道

Gangneung + Wonju = Gangwon-do

The city of Gangneung, of all places, is the coffee capital of South Korea.

If you’re uber familiar with South Korea, most of these cities are not the biggest cities in their own Provinces. In fact, most Koreans would have trouble locating where Na-ju and Sang-ju are on the map if the city names were hidden—I had trouble finding Sang-ju, Na-ju, and Choong-ju. The Province names were established mostly in the 12th and 13th century, and those cities were the biggest or politically influential towns/cities at the time. Hence the naming.