Korean, the Language with the Largest Vocabulary in the World

According to the US Department of State, Korean is a Category IV “Super Hard Language” to learn for English speakers. And there supposedly was some discussion about creating a whole new Category V just for Korean some time ago.

Grammar, verb conjugations, pronunciation, honorifics… And then there is this.

Graphic of the day.

Almost twice as many as the language with second most words. I knew Korean would be up there on a list such as this, but I had no idea it would be at the top. By a wide margin, no less.

This seems like the appropriate time to say something like I pity those of you who are studying Korean or thinking of learning it. But at the same time, I hope this does not discourage you from it. Take pride in the fact that you’re tackling a very unique language that is very rich, but challenging.

I got curious. How many Korean words would I know? Korean linguists estimate that an average Korean person knows about 20,000~25,000 words. Of which they use about 5,000 in everyday conversations. About 9,000 are required for reading and understanding news articles and novels. Probably a thousand more for scholarly writings.

Compare those numbers with an average American person having just about the same English vocabulary at about 20,000, and using 5,000 of them in everyday life. 8,000 to 10,000 needed for enjoying novels. 15,000 for Shakespeare.

These numbers are not only comparable, but eerily similar. Maybe that’s a universal threshold for “being fluent” in a given language (not that having a big vocabulary means that you’re fluent). That would be an interesting graduate level study in linguistics or psychology.

At any rate, I wanted to show you today why the Korean language has so many words and why it is so difficult to translate certain literary works into other Indo-European languages.

First off, the let’s state the obvious. Korean vocabulary often times have two words that mean the exact same things—one a pure Korean expression, and the other Koreanized iteration based on Chinese writings. (I’m going to assume that most of you know how to read Korean.)

고맙습니다 (pure Korean) = Thank you.

감사합니다 (borrowed from Chinese, “感謝”합니다) = Thank you.

How about this?

밥을 먹다 (pure Korean) = to have a meal

식사하다 (borrowed from Chinese, “食事”하다) = to have a meal

Second, the honorific forms of certain words that mean the same thing.

나이 = age (when asking someone who looks younger than you)

연세 = age (when asking someone who looks older than you)

춘추 = age (when asking someone who looks older than you in the most formal way)

So, what is usually one word in other languages is three separate and distinct words in Korean.

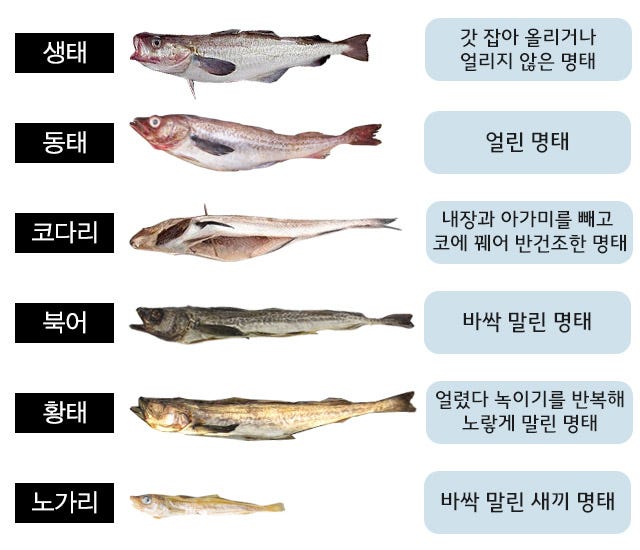

Third, different names for different states of a same thing.

Pollock (명태) used to be (not anymore) the most abundant fish around Korean coast. This fish is known by so many different names that even Koreans, including myself, are confused by them—and most of these names have been in widespread use for a long time.

From the top,

when it’s freshly caught, it’s 생태

when the fish is frozen, it’s 동태

when the fish is gutted and half-dried hung through its nose, it’s 코다리

when the fish is completely dried, it’s 북어

when the fish is repeatedly frozen and thawed over 20 times during winter and retains yellowish color, it’s 황태, but when the fish turns dark brownish during this process for some reason, it’s 먹태 or 흑태 (not pictured)

when the young fish is caught and dried, it’s 노가리

You get the idea. And there are about 12 more of these different names for the same damned fish, depending on where they were caught, what month they were caught and et cetera.

Don’t get me started on the counting system. And I’m not even talking about the numbers themselves, which in and of themselves cause headaches for Korean learners, I’m sure. I’m referring to the different units of counting for different things. Words like pair, bushel, piece, head…, not measuring unit words like kg, lbs, ton, inches, yards…

In Korean, these are called 단위명사, literally “unit nouns.” How many of these types of words do you know in English? I can’t think of more than a dozen, although I’m sure there are many more.

According to the Korean dictionary, the official number of unit nouns is 460.

개: the most common form, usually goes with any inanimate objects, the English equivalent would be “piece” (사과 두 개 = two “pieces” of apples)

권: counting unit for books (책 다섯 권 = five 권 of books, can’t translate “권”)

그루: counting unit for trees (나무 세 그루 = three 그루 of trees, can’t translate “그루”)

송이: counting unit for flowers (장미 한 송이 = one 송이 of rose, can’t translate “송이”)

명: counting unit for number of person(s) (but there’s another honorific form that means the same thing, which is 분)

마리: counting unit for animals (개 두 마리 = two 마리 of dogs, can’t translate “마리”)

켤레: counting unit for shoes or socks (신발 한 켤레 = one pair of shoes)

Then there are specialized units for counting things for sale at markets. These words are sometimes on the Korean proficiency exams for foreigners. This just isn’t fair because not many Koreans know this!

손: counting unit for moderately sized fish like mackerel (1 손 = two fish)

접: counting unit for vegetables or fruits (1 접 = 100 pieces)

축: counting unit for dried squid (1 축 = 20 dried squid)

Now you see why the Korean word count starts adding up real fast.

Then you add in the 사투리. In a country that’s quarter the size of California, there are at least 5 different regional dialects. These are not like the southern expression “y’all” in that almost all Americans understand what it is when they hear it. We’re talking about completely separate words, and if you’re from other parts (Provinces) of Korea, you wouldn’t know what these are.

For instance, I saw recently a TV quiz show that showed this following graphic.

The words denoted in orange are different dialects of the same word. What is the standard word that you all know? was the question. The answer was 바보 (stupid, idiot). As you can see, there are no two words that are alike. Since I’m from 경상남도, the southeast, I knew right away what 추꾸 was, although I haven’t used or heard of it for over 40 years. Boy, did that word bring back memories…

What is the English word for what’s shown above? Shimmer? That doesn’t quite do it, right? Shimmer or sun(moon)light reflected off of water would be more accurate. Similar way of describing this in German, French, Chinese and Japanese. In Korean, this is called in one word,

윤슬 (a pure Korean word—I’ve seen this word used as people’s names a few times lately.)

I’m well aware that all languages have this sort of very unique and directly untranslatable words. But I brought this up to show you something else. There is a synonym, another pure Korean word,

물비늘

= 물 (water) + 비늘 (fish scales)

The combination of these two words works, right?

Also, you can have two independent words, put them together, and create a whole new word that means something completely different. You’ve seen a few examples of this in my previous post about Korean expletives.

산 (mountain) + 책 (book) = 산책 (taking a walk)

나 (I, me) + 물 (water) = 나물 (edible wild plants and vegetables)

There was also something else that’s highly technical that made Korean and Japanese to have such a high word count but we’ll skip that part (you can look up features of “agglutinative” vs “fusional” languages).

Paul Carver, on the left, is a British translator of Korean and Khaina on the right is a French translator. The title of this YouTube video is,

Korean, the Language of the Devil among Foreign Translators.

During the interview, Khaina flatly says it’s much easier to translate French to Korean than Korean to French. She asks, what do you say when a certain food is spicy? Spicy? Hot? Not much else, right? But in Korean, there are…

맵다

얼큰하다

칼칼하다

매콤하다

맵씰하다

알싸하다

얼얼하다

There are words of varying degrees of spiciness and descriptions of how the spiciness hits the throat and/or tongue differently.

Back when I was living in Seoul in the 90s, I had a part-time gig at an international marketing company doing simultaneous interpretation. One day, they invited a target group of Korean ladies in their 30s and 40s reviewing some American snack item. I think it was some potato chip from Nabisco. I had a hell of a time interpreting what the ladies were saying.

고소하다

느끼하다

I was so stuck at these two descriptions that one of the Korean managers helped me with “savory” and “greasy.” But that’s not what those words mean, I muttered. The Korean manager who’s obviously been around the block a few more times, after the meeting, said to me, “I know. But that’s the best we can do.”

The point of today’s story? Korean is a difficult language to learn.

Oh, no wonder it's taking me years to learn!!