Being older (but not necessarily wiser) automatically commands respect in Korea and other Asian countries. I personally have a slight issue with this Confucian “rule” because of some people willfully abusing it, but in general practice, I think it’s okay. I’d much rather have that than youngsters displaying none in certain societies.

I’m sure those of you who are studying the Korean language are finding out that the vocabulary and the vernacular when addressing elders and those in socioeconomically superior positions is decidedly different in many situations.

For instance, to eat is (this is not a conjugation, they’re all separate words)…

먹다 (meok-da) when talking to people of similar age group or younger

들다 or 드시다 or 잡수시다 (deul-da, deu-shi-da, jahp-soo-shi-da) when addressing people of older age

Korean is replete with this kind of honorifics, amount of which is probably unmatched anywhere in the world.

Language is one thing but how to behave and act toward or in front of elders is a whole another matter—the “intangibles.” Let’s take a look at a few of them today with an emphasis on the table manners.

One of the biggest cultural shocks—an unmitigated shock—came when I learned that a son-in-law could call his wife’s father by his first name. To any Korean, this is unthinkable. For those of you who may be dating a Korean (or Asian) boyfriend or girlfriend, you would do well to remember this.

It is proper for me, as son-in-law, to address my wife’s parents as

아버님 (father-in-law) and 어머님 (mother-in-law) or,

장인어른 (father-in-law) and 장모님 (mother-in-law)

The latter is only for sons-in-law, not for daughters-in-law, and more formal but can sound a little distant. I myself prefer 아버님 and 어머님, and that’s exactly how my wife addresses my parents.

This naturally leads to table manners when eating with elders. The list is not short, but many are commonsensical, such as not making too much noise with your utensils, not using them as musical instruments, chewing with your mouth closed and things like that. I’ll cover what’s not so intuitive.

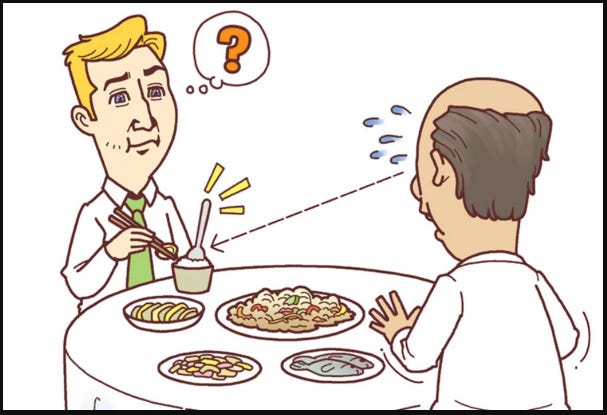

Don’t be the first person to reach for food. In fact, don’t even touch the chopsticks until the head of the dinner table has eaten something (you can, but just to be on the safe side). My kids, all born and raised in US, still won’t touch anything until their grandfather has started eating, although my dad has continuously said that it’s okay, just go ahead and eat.

Unlike Japan and China, you’re not supposed to hold the rice (or soup) bowl in your hand close to your mouth. In the old days of Joseon up until a few decades ago, that was how street beggars ate, and you obviously don’t want to replicate that.

In Japan, slurping when eating noodle type foods is actually encouraged (there actually is a reason why they do this), but never in Korea. Don’t slurp.

Don’t hold the spoon and chopsticks together. Only one utensil at a time. An even bigger no-no is holding one utensil in the right hand and the other in the left hand at the same time (unless of course you’re a steak restaurant in Seoul). Also, it used to be such that you weren’t allowed to use your left hand when eating, but that rule is pretty much gone these days.

And never do this with your spoon or chopsticks. That’s reserved for the dead.

Moving on to drinking manners.

Having an alcoholic drink with elders or superiors requires another set of protocol. Using soju as an example, when an elder offers you a drink, don’t refuse. Hold the soju glass with two hands and take it. If you can’t drink for whatever reason, accept the “offer,” pretend that you’ve tasted it a little and put it down. That’s okay.

(In the old days, there was this sort of unwritten rule that you had to gulp down the first glass in one shot and offer the same back to the elder as a “show of appreciation” but not many people do that anymore. I had to begrudgingly do it many times while I was in my 20s.)

Let’s say I organize a group tour of Korea among those of you who’d be interested. We meet at some barbecue restaurant in Seoul and have dinner together with soju. The immediately above picture describes how we would pour and receive drinks. Regardless of age, because we’ve never met before, both parties should be using two hands, out of respect for each other.

Don’t pour soju (or beer) while the glass is sitting on the table. If you grab the bottle as if you’re about to pour a drink for someone, they will invariably hold his/her glass up. You have to reciprocate when someone’s offering you a drink. Wine’s got a life of its own, so this rule doesn’t apply.

When actually drinking, hold the glass with two hands, turn and face away from the elder of the table, cover your mouth with one hand, then drink. Even in a very casual setting, for instance me having a beer with my dad at the table, I’ll still turn away a little (and I’m 56!). And this is with my dad having been the most gentle, easy-going, casual, no-unnecessary-bullshit kind of a guy all his life. But let it be known that this practice is actually debated whether it is proper or not. Might as well follow it, just to be safe.

I know that there’s some talk of having to cover the label of the soju bottle with your hand when pouring drinks for elders. I had vaguely heard of this a long time ago and actually looked it up, but this seems to be baseless.

If you follow these table manners in Korea, you will definitely earn some style points with the locals.

You never fail to entertain while educating. 건배!