In 2007, the city of Seoul designated 43 hanok (한옥, traditional Korean homes) in northeastern part of Seoul to be demolished and completely rebuilt because they were deemed to be “too old.”

A group of the neighborhood’s residents, led by one particular hanok enthusiast, sued the city and finally won after a long legal battle. The hanok village was saved from the claws of typical administrative ineptitude. In an ironic twist after the lawsuit was over, the defendant in the case, the Mayor of Seoul, awarded this guardian of hanok with an Honorary Seoul Citizenship. His name?

Peter Bartholomew. Ex-US military and Peace Corps volunteer who fell in love with hanok and lived in one for almost 50 years before he passed away in 2021.

It’s probably easier to see the features of the traditional Korean architecture by comparing it to the Chinese and Japanese architectures. One isn’t “better” than the other, for the style of construction largely obeyed those countries’ natural conditions.

It’s not terribly obvious, but can you spot the difference in the Korean architecture? (Royal palaces are used as examples, but the same applies for common homes also.)

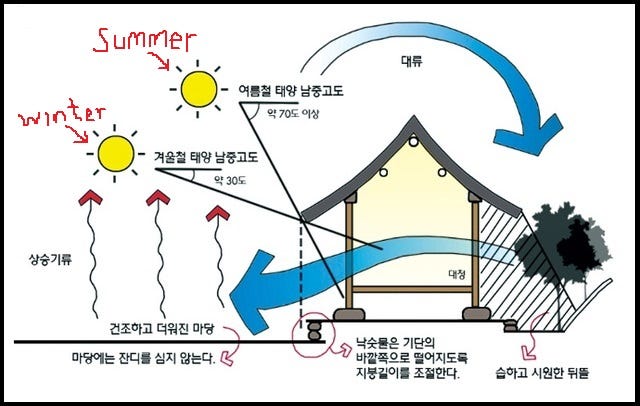

Here is a graphic that I found that should give you a good hint.

Purely out of curiosity, I’ve asked ChatGPT what sets the Korean traditional architecture apart from the Chinese and Japanese, and it gave me a few very generic answers. Not very insightful nor satisfactory. To quote one of the answers from ChatGPT directly (and this won’t ever happen again),

**Sloping Roofs**: Unlike sharply curving Chinese roofs, traditional Korean roofs have a gently sloping design. The modification from the Chinese style resulted in a more harmonious and serene appearance.

The top of the roof line is straight for the Chinese and Japanese architectural styles whereas the Korean roof line is slightly curved downward (or inward). This has roots in the old Korean building philosophy, “there are no straight lines in nature.”

Where have you heard this before? Perhaps Antoni Gaudi took a page right out of the Korean architecture textbook? Before you laugh it off, I’m here to tell you that the chances of that actually happening isn’t zero, for there’s a disputed precedent with Leonardo da Vinci’s interpretation of old Chinese painting in his famed Mona Lisa. Let’s see ChatGPT come up with that kind of analysis!! (stay tuned).

There is actually some math that’s involved with how the Korean roof and its roof tiles (called 기와, gih-wah) were developed. I won’t get into the details of it here but the slope of the roof and the roof tiles are in the shape of a cycloid—curve line traced by a point on a circle when it rolls along a straight line.

The point of having the roof (and tiles) built in the shape of a cycloid is to have the rain (or snow) water to drain as fast as possible, to cause less damage and lengthen the life of the tiles.

Also, you see the corners of the cheo-mah lifted slightly up. That was to let sunlight in as much as possible to help keep the pillars dry after rain.

This feature isn’t uniquely Korean. It’s everywhere in East Asian countries, but built at different angles for scientific reasons. As you go down further south in terms of latitude, say Vietnam in relation to Korea, this “lift angle” gets sharper upwards to let in more sunlight because the Sun’s day arc is lower than that of Korea’s during winter months.

Let’s move on. Remember from my previous posting about Korean homes having huge windows or openings to the outside? Going back to the house shown at the top of this post, look at the yellow circled objects. Those are doors/windows that are folded, lifted up, and tied to the underside of cheo-mah (처마), blurring the line between the outside and inside of a home.

This wasn’t just a cute idea—it had a real purpose. From my previous posting, I had asked you to remember this opening to the backside of the house.

If you were to look at the house from the side, this would look like…

There are a lot of things happening here, but let’s first focus on the two blue arrows. Because a typical hanok is almost exclusively built so that it faces south, and has big openings both in the back and front of the house, the air circulates freely like the graphic shown above. Also because of the positioning, the back of the house was almost always shaded, and with trees it had cooler air. So, this acted like a natural air conditioning system. (it still gets really hot and muggy during summer in Korea.)

Not only that, because of seasonal changes, the sunlight during summer months would be blocked by the cheo-mah whereas the sunlight during winter months would come directly into the house, helping with natural warming.

Then, there’s the heating system called ondol (온돌). Again, remember how a Korean house was built so that there was some space between the floor and the ground so that air could travel through? This was the “other” purpose that I’ve alluded to in the previous posting. As I understand it, this ondol system exists only in Korea.

So, there’s this sort of “kitchen furnace” outside the house called 아궁이 (ah-goong-ih) where you use the firewood to cook and that heat would travel through the air duct underneath the house floor made out of stone to warm up the room attached to the 아궁이. It’s a very efficient way of warming up the house in the bitter cold of Korea, but this heating system had a fatal flaw.

Because of this ondol (literally “warm stone”) system, you could only build homes that were single-story high. Some historians argue that this was one of the reasons why Korea “developed” at a snail’s pace or didn’t at all for over 2,000 years. The logic behind that argument is that people need to live close by, or have a high concentration of people within city limits, cooperating and working together to advance a civilization, but because all buildings had to be what we in the US now call “Single Family Residences,” this was not possible. Up for debate, I’m sure.

** this AI image creation thing is simply amazing.

There are so many other aspects of Korean architecture that I simply couldn’t go into because of my lack of knowledge. But with that, I’ll leave this topic with two other thoughts. In constructing the Royal Palace, Baekje (백제, 18 BCE ~ 660 CE) and Joseon Dynasties (1392 ~ 1897) believed in the same philosophy known as…

儉而不陋 華而不侈 (검이불루 화이불치, gum-ih-bool-loo hwa-ih-bool-chi)

This saying has been translated many different ways, but this is my own. Frugal but not shabby, exalted but not extravagant.

And of course, how could I forget Peter Bartholomew? As a former director of the Royal Asiatic Society Korea Branch, Mr. Bartholomew did tireless work on not only preserving the Korean architecture but to enhance and educate the beauty of it. He even did research on the old Korean geography and discovered something that no other Korean historian/scholar had.

Here is a YouTube video of him giving a lecture about hanok. This is in English, but Mr. Bartholomew spoke very fluent, almost perfect, Korean. (there are YouTube videos of him giving lectures about hanok in Korean to Koreans also). Rest in peace, Mr. Bartholomew.

![한옥문화촌 경기도 미금시 민속박물관. [중앙포토] 한옥문화촌 경기도 미금시 민속박물관. [중앙포토]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!sTc5!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Ff7011ee8-29d7-4a9a-98ab-b5f1fc22b270_560x448.jpeg)

After reading this essay, erudite is the word that came to mind. You must have done a fair amount of research to present in such a brief essay so much background on Korean architecture. Your allusions to math, geography, climate/weather, heating systems and airflow, roof tiles and stone foundations could provide material for many semesters worth of studies and exploration on construction practices. The Vietnam photo is a nice addition for more comparison to demonstrate the effects latitude played on building design. It makes me appreciate human ingenuity. 감사합니다