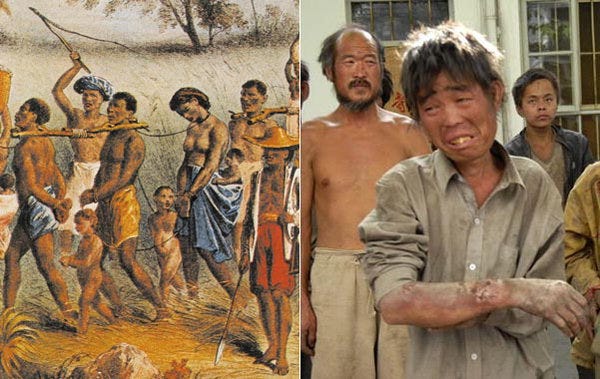

One of the most diabolical things that humanity has ever created and endured for such a long time, in my opinion, is slavery. Some would argue it still exists today under a different name and a different look.

Only about 10 years ago in a remote island in Shinan (신안) area of southwestern Korea, a group of intellectually challenged people were found to have been put to years of forced labor at salt fields without pay. They were given minimal food and shelter for subsistence and no other care, often times beaten and even stabbed. Also, everyone at the salt fields were wearing the same red sweatpants in case they try to escape. They would be easily found.

To discuss today’s topic from a historical and comparative perspective, I need to first clarify the words used because the old “Servant” class of Joseon and previous Korean dynasties are in many ways different from the European and American slavery—and similar in a lot of ways too.

For “Slavery” or “Slaves,” we use the word 노예, no-yeh. Korean servants, however, were always called 노비, no-bi, throughout all of its history. There really is no discernible difference between the two words themselves, both meaning quite literally, “servant.” But Korean historians are adamant that they do NOT translate the word no-bi as “slaves” nor do they agree on any English word that is equivalent. So, we just go with 노비. And throughout this post and my future posts, I’ll use the word “nobi.”

Okay, with that out of the way, let’s consider the class system of Joseon. Wikipedia has this table. You don’t have to memorize all the names, but just know this—the top 3 are okay, the bottom 1 isn’t.

What is not shown here (and not an official “class” of people) is the members of the royal Yi family that were above the yangban class.

We’ll someday take a closer look at the top three classes, collectively called as “yang-in (양인)” but for today let’s concentrate on the “nobi” of “lowborn” people. For reference, baekjeong (백정) are butchers (considered the lowest of the low), mudang (무당) are Korean shaman practitioners, gisaeng (기생) are female entertainers (not prostitutes, as many seem to think) at private clubs of the day.

The “no” of nobi are the male servants and the “bi” are the female servants. If you’re into history-based K-dramas, you might have heard other words referring to nobi. 종 (johng) is as same as nobi and there is this other word 머슴 (would be transliterated as “meo-seum,” pronounced “muh-sm”) that’s slightly different. 머슴 is a contract-based laborer to a yangban, sort of like a “free agent,” if you will. Records indicate that even yangban class people worked as 머슴 to other well-to-do yangban when they fell on hard times.

You probably have a stereotypical imagery of nobi in your mind—dressed in dirty white clothes, unkempt face and hair, not enough feet covering, working day and night at the owners’ beck and call… And you would mostly be right.

If we were to do a compare and contrast analysis of the western slaves to the Korean nobi, a few things pop out right away. Like the slaves of western culture, nobi were…

considered properties of their owners,

thus had no freedom (well… yes and no as we will see in a bit),

put to hard labor,

not allowed to have last names,

born as one and died as one (in most cases until the late 18th century).

But things start to appear different when you consider the fact that King Sejong (there he is again) guaranteed nobi’s legal rights by protecting them from the owners’ indiscriminate punishments. For instance, on top of guaranteeing nobi’s property rights, the Joseon Court during Sejong’s reign passed a law saying that if an owner kills a nobi without cause, that owner will be subject to 60 to 100 caning called 곤장 (gohn-jang).

Yi Sook-beon (이숙번) was one of the top officials of early Joseon who helped found the new dynasty, therefore given enormous power, authority, land grants, nobi grants, among other benefits. He, during Sejong’s reign, tried to rape one of his bi (female servant) who was 14 years old at the time and was met with a knife blade to his forehead, almost killing him. This 14-year old bi, named 소비 (Sobi, no last name), was ultimately exonerated by the Joseon court officials, led by King Sejong.

** side note: There is a small group of historians who claim that Sejong wasn’t all that great of a King because he enacted a law that eventually led to the number of nobi in later Joseon time to balloon to 50% of the whole Korean population. Not false, but not entirely true either. One of those grey areas.

One day I’m going to have to talk about someone named Jang Young-shil (장영실), the most celebrated “mechanical engineer” of Joseon dynasty who lived during Sejong’s time. Jang’s mother was a nobi in Busan area, so he of course was a nobi as well. But his scientific and engineering skills were so outstanding that King Taejong (Kill Bang-won and Sejong’s father) hired him at the royal court in Hanyang (Seoul) and Jang’s creations so ingenious that Sejong not only made him a yangban status but a very high-ranking court official. There are records of “precedents” of such things happening when Sejong was discussing the matter of Jang’s nobi status with the court officials, signifying that there were previous instances of nobi shedding their “lowborn” status and becoming part of yang-in, or even a yangban.

There were largely two types of nobi—one called 관노 (gwan-no) and the other 사노 (sah-no). The former is public service nobi, owned by various local magistrates, and the latter privately owned nobi. Gwan-no lived in their own homes and had more or less a “9 to 5” job.

Then there were two types of sah-no—the ones who lived with the owner and the ones who lived outside, in their own homes. The nobi we’re sort of accustomed to seeing because of the K-dramas are the ones who lived with the owner. It is said that the ones who lived outside had a lot of freedom—it was like go-to-work-then-come-home type job that isn’t all that different from what we do today.

Not only that, most of the nobi who lived outside tilled their owners’ land, paid the owner with a fixed amount of crop, and kept the rest as their own assets. And the very surprising thing about this is that nobi could own other nobis! At this point, we’re getting into a blurred line between an actual nobi system and contract labor. This is a very important point because in later years, some of them accumulate considerable wealth as to be able to buy their way out of “lowborn” status.

Also, whereas American slaves weren’t allowed to learn how to read and write (although some did), there are records of many learned nobi who could read, write, keep books, make calculations, engineer things like the abovementioned Jang, and even become a full-fledged poet. So much so, some of them becoming their owners’ friends.

But by any means, I’m not trying to romanticize about the ordeal these poor people were put through. Their lives, by all accounts, were full of hardships, pain, and suffering.

What is more, they didn’t have what you would call normal names but were given very demeaning and inhumane ones, like the Korean equivalents of…

broomstick (빗자리), the months they were born in like 이월, 사월, 시월, bitch (as in a female dog, 암캐), testicles (개부리), dog poo (개똥이), pig (도야지), diarrhea (물똥이), fart (방귀), insect (벌레), animal reproductive organs (거시기)…

For yangban class, there were largely two types of assets—land and nobi. Land doesn’t grow or expand by itself, but the number of nobi can grow whenever they marry and have children. Although it’s hard to put a dollar figure on it, one estimate shows that one nobi was worth about 10 million KRW (~$7,000 USD).

Some of you may have seen the popular K-drama called 추노, the Slave Hunters, that came out about 15 years ago. It’s a story about runaway nobi and the hired hands to track them down. The drama is generally very well-received, but the above screenshot is often used to make fun of how misleading these TV dramas can be. She’s supposed to be a nobi with a dirty face and clothes but look how white and perfect her teeth are.

It is also notable that poor yang-in (any one of the 3 classes that are not nobi) would frequently marry people of nobi status who are in relatively affluent economic status.

And because nobi’s children were also nobi, the total number of them kept growing throughout Joseon. No hard numbers obviously, but estimates range from as low as 30% up to even 50% of the entire Korean population around mid-17th century being classified as nobi.

This was a problem for Joseon indeed because nobi were exempt from taxation and military service. After two horrific wars that Joseon had to suffer through in late 16th and early 17th century, the Joseon court started offering “buy your way out of lowborn status” opportunity to replenish its treasury.

But obviously you don’t go from lowborn class straight to yangban class, no matter how rich of a nobi you may have been. But here was another problem if you’re of a lowborn person that just bought yourself out and became a sang-min or jung-in. Now you have to pay taxes and serve in the military if you’re called upon. Paying taxes is one thing but everyone wanted to avoid the military service, especially when the whole country was still reeling from the recent wars and the devastation still fresh in their memories.

But there was a way to avoid the military service, which was to pay a special tax in lieu of serving in the military. And guess who was exempt from both. Yangban class. It is thus no wonder why everyone wanted to become of a yangban class. Then, how do you become a yangban? You either pay a great amount to buy one, or pass the national civil service examination called 과거 (gwa-geoh). And in order to pass that exam? Study, study, study.

You see, this comes back full circle with the modern-day focus on education in Korea, some parents acting certifiably crazy by sending their kindergarten children to private calculus classes. Think about that for a moment. Never mind the basic arithmetic, algebra and geometry. 5 and 6 year old kids are learning high school senior level calculus.

So, this pressure to educate your kids so that they can become someone is very deeply rooted in Korean society.