This is going to be a very sensitive subject matter for some. Before anything else, I apologize if I offend anyone in any way—please understand that it’s not my intention to hurt anyone, as I’m trying to discuss what has already been reported as truthfully and honestly as I can. (and please scroll down slowly, for there might be spoilers as you continue with the story.)

A few months ago, one of my subscribers had suggested that I look into the issue of foreign adoption of Korean babies and children. I was reluctant to, but as fate would have it, one of the documentary TV shows I sometimes watch tackled the very issue shortly after the suggestion was made. And ever since, I’ve been trying to gather some definitive information but couldn’t. The information is all over the place in terms of numbers, stories, the adoptees’ journey back… and every article/writing seems to end with the same damned conclusion—the government needs to do better with regulation and oversight. And there was something sinister happening behind the curtains, which I’ll get to.

Understanding how things were in Korea back in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s (and probably 80s too), it is no surprise that there is a wide discrepancy between what the government says the number of children who were adopted by foreign families since the end of the Korean War is (169,454 at the end of 2021) and what the independent researchers say it is (closer to 250,000).

What stood out the most to me (shocked me, in fact) is that the highest annual number of foreign adoptions of Korean babies occurred in 1987. One year before the Seoul Olympics, and during the time when the country was drunk in its own celebration of the never-before-seen economic prowess, not unlike the Japanese bubble economy of the same time frame. As you can see in the following chart, the number was still above 2,000 per year just 20 some years ago—remember, these are “official” numbers put out by the government and is thought to be considerably higher.

Some of them were voluntarily given up by their parents because of economic hardships, some were simply orphans, some born out of wedlock and abandoned…

Then, there is the case of then-6-year-old 신경하 (Shin Gyong-ha) of Cheongju (청주) city.

In May of 1975, the six-year-old girl disappeared while playing in front of her house with her friend. Her mom had gone to the local market with Gyong-ha’s little sister and baby brother that was born a short while ago.

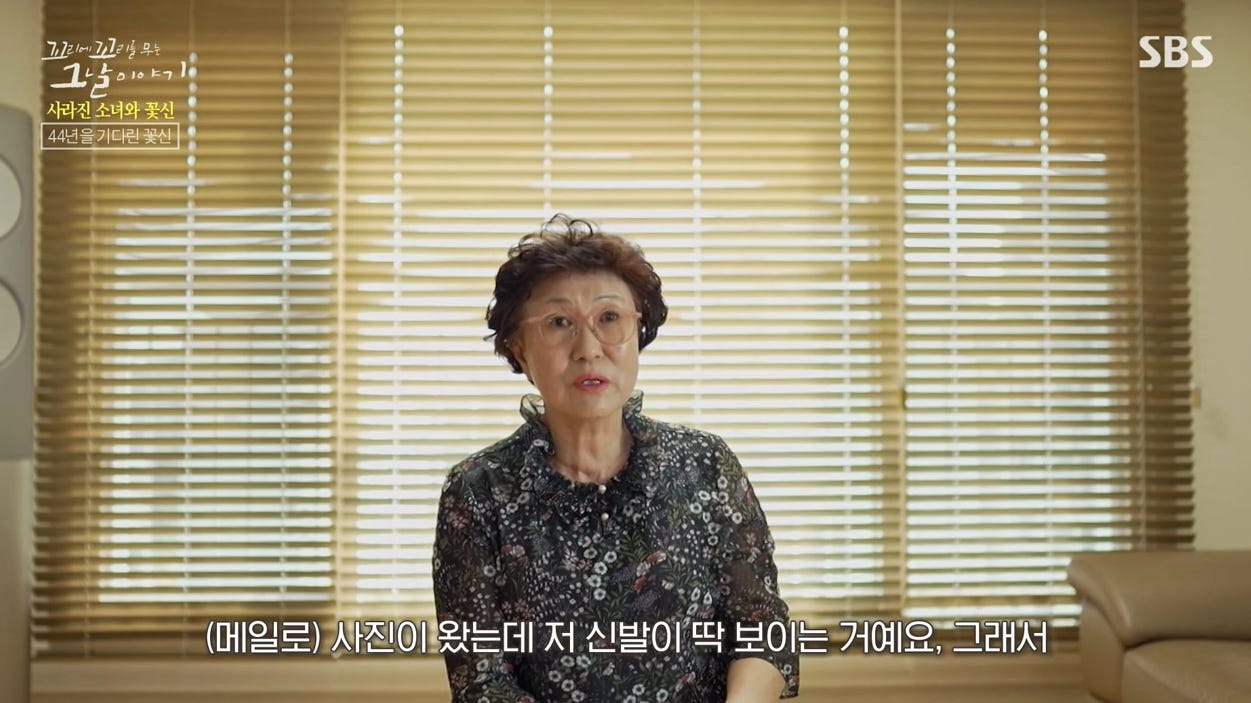

In interviewing with the TV documentary producers, the mom (above pic) talked about the shoes Gyong-ha was wearing in particular when she went missing because the impressionable 6-year old had kept pestering her mom to buy a pair of “flower shoes” that her neighboring friend had.

After weeks and months of searching in vain, mom reluctantly sought help from a Korean shaman. The fortuneteller had told her, “It will take 16 years before you see her again.” Not knowing whether her firstborn daughter was even alive, she had to keep on living because she had two other children. She worked and worked as a hairdresser and asked anybody who would listen if they had seen a girl that looked like Gyong-ha. About 10 years after Gyong-ha went missing, she got a call from the police and was asked to identify a body that seemed to fit the description of Gyong-ha. It turned out that it wasn’t. Then, there was a national newspaper ad campaign looking for missing children.

And similar search efforts on the cover of popular Korean snacks. It never ended. 10, 20, 30 years…

In 2016, she was a part of a nationwide search campaign for lost children in Korea over the internet. The panel says, “Shin Gyong-ha, female, 47 years old now, missing since May 9, 1975. There is a burnt scar on her left side below the belly button. Short black hair.” Now, mom is well into her 60s and Gyong-ha is almost 50, if she’s alive.

Then, in one morning in October of 2019, 44 years after Gyong-ha went missing, mom gets a call on her cell phone from a number she doesn’t recognize. (In Korean) “Are you Gyong-ha’s mother?” “Yes, I am. Who is this?” “I’m from an organization called 325 KAMRA and I think we’ve found your daughter. In the United States.”

The initial thought mom had was that it was a prank call. Then she suddenly remembered that she had sent in her DNA testing kit with one of the services that stored such information to link up with foreign DNA organizations in 2016.

The representative from KAMRA had said that they had found someone in the US with 90% match in DNA testing. “Adopted? To the United States?” Mom later admitted that it was a scenario that she never even dreamt of. The initial conversation ended there, with the KAMRA representative saying, “We will let you know more tomorrow.” Mom obviously couldn’t wait that long. She said that she called, called, and called again until the KAMRA rep finally answered, and was able to get this purported Gyong-ha’s contact information. The email address.

Mom asked her son who could communicate in English to write an email to this supposed Gyong-ha. And almost immediately, a reply. With an attached file.

Can you tell which part of the child’s picture mom’s eyes were fixated on? Those “flower shoes.” Then, she knew. She knew it was her.

And the following is their first phone conversation, recorded by MBC (Munhwa Broadcasting Company), re-broadcast by SBS (Seoul Broadcasting System). (to anyone who has the rights to this footage, please don’t claim it and take this down, for the sake of public service.)

“Gyong-ha… how did you even end up in the US? I can’t really speak any English. Brother, brother, talk.”

They both wanted to fly to each other’s location, but it was decided that Gyong-ha was coming to Korea just as soon as she could. Mom immediately started studying English, for Gyong-ha couldn’t speak Korean at all.

Mom said that there was one sentence that she practiced very hard because she wanted to say it clearly to Gyong-ha when she finally saw her. See if you can make it out. It’s at the very end of this footage.

As Laurie Bender, Gyong-ha is a nurse in Indiana and herself mother of her own daughter Kaley, who you saw in the above video as well.

Now, let’s try and find out what happened.

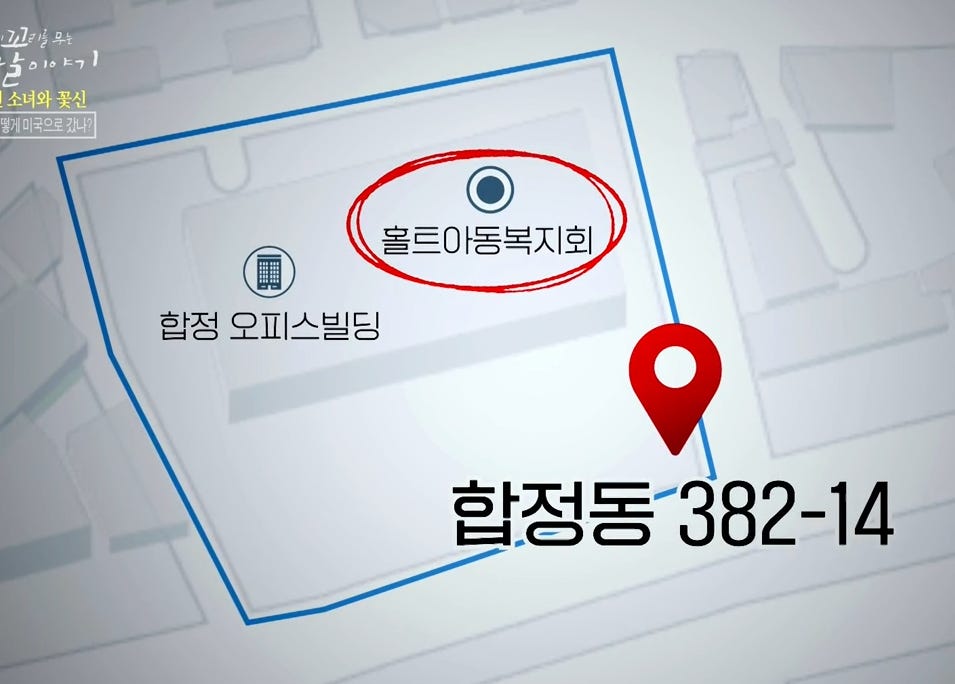

This is the copy of the travel document that Gyong-ha had in her possession when she was adopted to a loving and caring American family. It says she was born in Seoul, not Cheongju, which is where she’s actually from. And do you see that address there printed? That’s a non-existing address in current Korean map. However, let me show you this.

That triangle is where the address points to when you search it in a Korean map service. Do you see that building right next to it? That’s a very well-known non-profit organization that has arranged for Korean war orphans to be adopted with foreign adoption families. And lest anyone connected to that organization come after me for some reason, I’m just a messenger. This is what the TV documentary showed.

And on the back of the photo that accompanied the travel document…

… it says, Baik Kyong-hwa (백경화). When the police back in 1975 looks for the missing Shin Gyong-ha (신경하), no wonder there’s no answer back from anywhere, right?

So, there it is. Gyong-ha officially left Korea on Feb. 4, 1976, some 9 months after she went missing.

(Getting a little too long, so I’ll summarize what had happened in May of 1975.)

Gyong-ha was playing in front of her house when some lady with fried chicken (expensive and rare food back then) approached Gyong-ha and asked, “Hi. You have a new baby in your house, right? Your mom said that she doesn’t want you anymore. So, just come with me.” This took place soon after Gyong-ha’s little brother was born (remember? the one who spoke English above).

And Gyong-ha was put on a train where she fell asleep, and when she awoke, the lady was gone. The identity of this lady is obviously unknown, but it is very strange that she knew exactly where Gyong-ha lived and that her mom had just given birth to a baby brother.

Gyong-ha was taken to an orphanage where she remembers she had given her name and age, but she was told that her new name was now Baik Kyong-hwa. Why Baik? The director of that particular orphanage Gyong-ha was taken to happened to be an American with the last name White. The color white in Korean = 백 Baik.

This is the actual copy of Gyong-ha’s registration papers at that orphanage—the broadcasting company was able to trace it back, based on Gyong-ha’s memory and discover this. Towards the bottom, item number 6, it says “Describe circumstances regarding becoming available for adoption:” And as you can all see, the “Abandoned” box is checked. Which of course we all know is falsified.

And the orphanage decided that Gyong-ha would be a good candidate for adoption to America. The case of Gyong-ha was now transferred to the above-named “Children’s Services” place that was shown on the map. And an official government document, saying that Gyong-ha is an abandoned orphan was produced—something that is unthinkable these days. Now, everything was cleared for adoption.

As painful as it is to look at, this picture is inside of a chartered airplane carrying over 100 babies to the United States for adoption.

It is only logical to ask, WHY has no one even tried to take Gyong-ha back to her family? WHY does everyone seem so eager to send babies for adoption to foreign countries? And who the hell was that lady?

The TV documentary brought up, without accusing any particular individual or organization, this fact. Towards the end of the 1980s, the adoption fee American (or European) families had to pay to the adoption services in Korea was $5,000 USD. It’s a lot of money today—can you imagine how much that was 35 years ago? To put that 5,000-dollar fee per 1 baby into perspective, the South Korean Per Capita Income during that time was $4,500.

You all can put 2 and 2 together at this point.

Let’s get back to Gyong-ha for some concluding remarks.

While she was growing up in the US, Gyong-ha kept drawing the same thing over and over again, to never forget where she came from. And she has kept this after all these years.

One day, Gyong-ha’s daughter Kaley apparently had asked her, “what was your real mom like?” And Gyong-ha couldn’t answer. And who do you think came up with the idea of DNA testing and registering it with one of the organizations like KAMRA? Kaley. 10 full years before Gyong-ha and Gyong-ha’s mom finally met at the Incheon International Airport.

I know if you read through the whole thing that you can’t help but get emotional and angry. Again, I apologize if I hurt anyone in any way. And if you know anyone that can use services like 325 KAMRA, please let them know. I’ll try to get back on schedule next week—release something on Sunday morning.

This is excellent reporting. Well done!

You've revealed an underbelly of adoption. As for that huge uptick in foreign adoptions in 1987, one might assume that people around the world were suddenly learning more about South Korea because it was in the news for the upcoming Olympics. Whether there was a nefarious black market suddenly established because of that spotlight, one can only hope not. Thank you for sharing the name of services like 325 KAMRA, https://www.325kamra.org

I also saw an informative documentary on Korean adoptees https://youtu.be/1eGyXcda-Cc?si=nMATgEIYPvCK5Db1 - "This conversation explores this little-known history and the eventual adoption of approximately 200,000 Korean children worldwide. The event features Professor Kori Graves, whose book, “A War Born Family: African American Adoption in the Wake of the Korean War,” explores how Black American soldiers came to adopt Black Korean children, in conversation with Korean adoptees Dr. Estelle Cooke-Sampson, Lisa Jackson, and filmmaker Deann Borshay Liem."